Annual Members Meeting - November 2018

Hello. My name is Anne Warner. Some of you know me. Most do not. I’ve worked with Peggy Larson on the Desert Museum’s Oral History Project for several years. My task this morning is to help Peggy introduce you to our very special project. We’re going to tell you a bit about how the project came about – and then we’re going to ‘tell tales’ from the Museum’s past!

The Desert Museum has a long history of working to preserve its history – starting with its founding Director, Bill Carr. Early on Bill Carr recognized the value of documenting the history of the museum. Arthur Pack’s secretary, Francis Colley conducted early interviews. Then in 1976, Bill Carr obtained a grant from the Weatherhead Foundation to hire an interviewer and transcriber to meet with early Museum supporters. Margaret Gerow conducting those interviews, interviewing key staff and board members. Those documents remained – even if a bit buried — in the Museum files for decades.

Then along comes Peggy Larson. As most of you know, Merv Larson, Peggy’s husband and one of the Museum’s early Directors, and Peggy were some of the Museum’s first residents’ in 1950s and the 1960s. They spent many a day – and yes, nights and evenings – entertaining the Museum director – Bill Carr, the various museum animal residents and visitors who ‘floated’ through. Merv and Peggy left the Museum during the tumultuous times of the 1970s But then in 1997 after retiring from Tucson Unified School District she came out and met with Nancy Laney, then acting Executive Director of the Museum. Peggy’s opening line to Nancy was ‘someone’s got to write your history’. Nancy’s response: ‘Fine, but someone’s got to find it first!’ - and so began the next phase of Peggy’s ‘life at the museum’.

Peggy came to work for the Museum in an official capacity as Librarian and Archivist in 1997 She spent a fair amount of time ‘unearthing’ and trying to organize Museum records. She then began the renewed task of chronicling the Museum’s development by conducting more interviews – staff and board members primarily. As a part of this research effort, Peggy also wrote and the Museum produced what’s now the iconic book on the Museum, Scrapbook.

At this point, Peggy’s interviews had been recorded on cassette tape, but not transcribed – and certainly not digitized. Recognizing the need to ‘enter the digital age’, Peggy began to look for help.

Enter me – stage left – in 2011, when I began to assist her with converting recorded interviews to a digital format and transcribing some of the older interviews. Then about four years ago, I turned to Peggy and said ‘you know many of those associated with the Museum are ‘disappearing’ on us – in some cases simply geographically — in other cases more permanently.’ And thus we began what’s become the third round of Desert Museum Oral History interviews.

Here’s a quick summary of interviews done to date:

- Total number of interviews: Over 110 interviews have been conducted.

- Early Interviews – 46 interviews

- More Recently - 64 Interviews

- So, who have we talked with?: Staff – Current & Former; Board Members – Current & Former; Docents & Volunteers; Community Leaders – and yes, your landlord, Pima County!

- Range of Ages: 19 to 94

Regrettably there are no known interview tapes/transcriptions of Arthur Pack, the other co-founder. There are, however, interviews of Phoebe Pack, Arthur Pack's second wife and active museum supporter.

Ok, let’s fast forward a few years – we’ve got all these wonderful interviews but we needed to find a way to share the ‘tales’ that came out of the interviews while preserving the privacy – and yes, sometimes unwitting candor — of the interviewees. So we came up with the idea of producing a series of Oral History Vignettes – which take the basic stories from the interviews and also tell the history of the museum — effectively serving as a bridge from the interviews to the vignettes using both text and photos.

We have lots more to go but the Vignettes currently posted on the ASDM web site include:

- Arthur & Phoebe Pack

- William ‘Bill’ H. Carr

- Hal & Natie Gras

- ASDM Amenities and Memories – featuring Food Services & the Gift Shop

- And then there was George (as told by Peggy)

- Art and Exhibitry — the ASDM Tradition Continues

- Bill & Beth Woodin Memorial Celebration

- ASDM Historic Photo Gallery

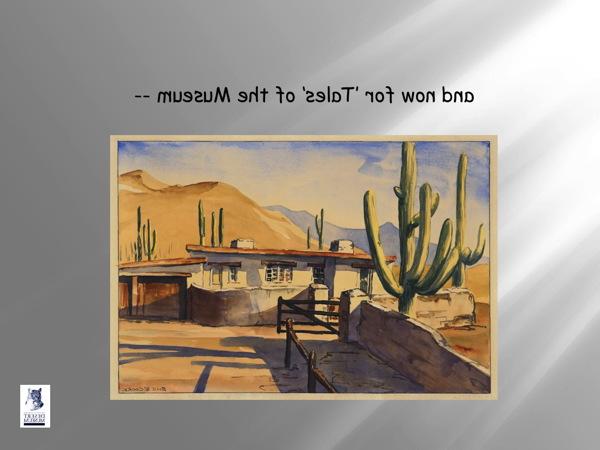

But part of the Oral History Project is simply having fun, so in celebration, we’d like to share tales of some of the animals and people who’ve made the Desert Museum what it is today.

So to tell tales – here is Peggy Larson

When Anne and I conduct interviews we use questions that briefly explore the interviewee’s role in relationship to the Museum, that is, staff, Trustee, member, or other. But for all we pose two thought questions: If you were writing a book about the museum, what would be its theme? The answer gives us a lead as to what that individual considers of prime museum importance. The second question is "What do you think the Museum will be on its 100th anniversary—what would you like it to be?" We’ve received many varied and thoughtful answers. But we are also recording many stories about the Museum’s development and the people and animals involved in its growth. Today I’d like to share with you some of my stories from the 1950s to the present that I have recorded for the Museum Archives.

My husband Merv was employed by the Museum and he and I lived in the stablekeeper’s house on the Museum grounds, having moved there in January 1953 when the Museum was just four months old. At that date the Museum was composed of the main building with a room of small animals, another with a few geological specimens, a line of large outdoor animal enclosures, and a path through the desert with a few plant labels. Bill Carr was living in the back rooms of the main building. There was no food concession at the Museum and Bill maintained his cooking skills were limited to questionable use of a can opener, so one of the qualifications for Merv’s job was that I cook dinner for Bill each evening. Considering my cooking skill level in 1953, I think Bill would have done better relying on his can opener!

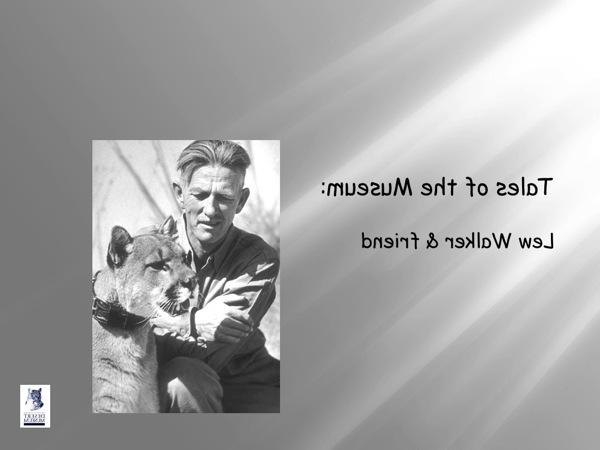

One day that spring a motorcycle roared into the maintenance yard in front of our house. I went out and introduced myself to its rider who turned out to be Lew Walker, an old friend of Bill Carr’s. I found Bill for him and soon thereafter Bill found me and said I should invite Lew to dinner that evening. Then he added, “But he only eats steak!” There was none of that in my miserable little refrigerator so an emergency trip to town was made and Merv was just building a fire for barbecuing it outside our back door when Bill and Lew arrived.

Lew announced he was an expert at cooking steak and took over the fire set up. Now Lew was the ultimate outdoorsman, having been exploring Baja and the Gulf since the early 1940s, having served as a Marine in the Pacific Theatre, and having written a government publication on Pacific island survival that he and others used to train Air Force personnel. So when Lew, while building the fire announced that the very best flavoring for cooking steak was adding some peccary dung to the coals, who were we novices to question him? And certainly there was no lack of peccary dung at the Desert Museum! A sufficient amount was obtained, added to the coals, and the steak cooked by an expert. It was delicious. Within a couple of years, Lew became Assistant Director under Bill Woodin and became an important figure in Mexico’s federal government ultimately providing protection for Rasa Island and eventually protection for all of the Gulf islands.

One day in mid-February Bill Carr received word that a mountain lion he had been expecting had arrived at the Tucson airport. He asked Merv to drive him in to the airport and invited me to accompany them. I was delighted to accept the invitation. When we arrived we found a smallish, animal-traveling cage surrounded by a small group of people. The cage had a screen covering one end and the lion’s face was looking out at the observers who were ‘oohing and ‘aawing over the lion’s “growling.” Actually it was a purring lion enjoying the attention.

This was a very friendly lion and Bill Carr and I talked to him all the way back to the Museum and he frequently answered us in friendly lion sounds. Arriving there we were convinced this was a remarkably friendly (and small) lion and Bill asked Merv and me if we’d like to go into the lion enclosure while the “small” lion was released. We were delighted to accept. In the lion enclosure the end of the traveling cage was opened. The lion eagerly began to exit and to greet us, his welcoming committee. To our astonishment he expanded as he emerged! Suddenly he grew longer, taller, heavier, and ever more lion-like than we had ever imagined. There we were three people and a lion in a lion’s cage!

Bill quietly but firmly advised us to head for the closed door of the exit: calmly, but quickly. Certainly we did not hesitate, but I’m sure if we had dared to look behind us, instead of straight ahead at the closed door, we’d have seen a lion with a puzzled look on his face wondering why his new friends were leaving so soon. That day the lion became George L. Mountainlion the First and he set the tone for the Museum for many years thereafter.

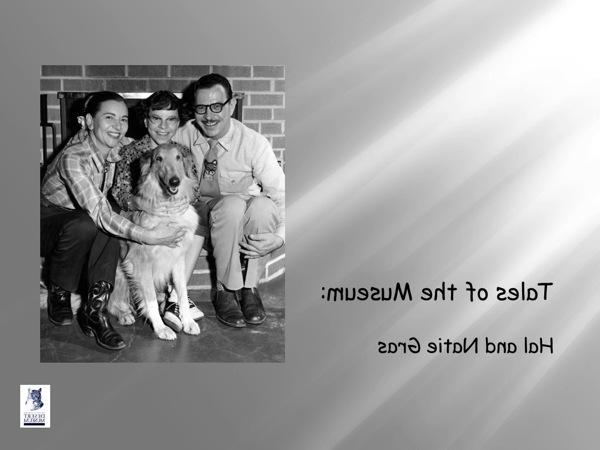

Another early arrival at the Museum was Hal Gras, who for thirty years was Captain of the Desert Ark and became Mr. Museum to generations of Tucson school children, as he presented animals to school classes and talked to children about the beauty of and care for the desert environment. One of the children’s favorite animals was La Vaga, a ringtail that had been born in a stored bomber at Davis Monthan, rescued, and then raised by Hal and his wife Natie. During each Desert Ark presentation before children (and sometimes adults, as well) Hal placed La Vaga on a child’s head and allowed her beautiful tail to drape down alongside the child’s face, a la Davy Crockett’s hat (in those days Davy was a standby on TV). Privileged, indeed, was the child so chosen to be called up in front of his peers and allowed to “wear” La Vaga.

A story Hal told had to do with La Vaga’s name. Actually it was La Vagabunda, or little vagabond. She was so named after her first visit to a TV studio at a young age, when frightened by the lights, noise, and confusion she escaped from Hal and immediately became lost in the station’s overhead wiring and ceiling. As Hal later told the story, he called on and was assisted in her capture by eight different agencies, including the local fire department. Of course George L. Mountainlion helped Hal by writing letters of thank you to all who assisted in her capture and La Vaga went on to become a friendly, loved member of the Desert Ark.

When our children were three and four a coyote at the Museum had a litter of pups which were not needed there so Merv brought one home for our kids and Bill Woodin took another. Raising the pup was somewhat similar to raising a dog, but with a few differences. The coyote was extremely alert and soon tended to play pretty roughly.

The Woodin coyote, living in a more wilderness area soon began at times to mingle with a wild group and eventually we took our Sammy out to Woodins to hopefully follow suit, which he did successfully. It was several decades later when we were interviewing one of the Woodin adult sons that we heard the story of their father, Bill Woodin the Museum’s Director, teaching Sammy the coyote to howl in order that the coyote might better fit in with his new wild family.

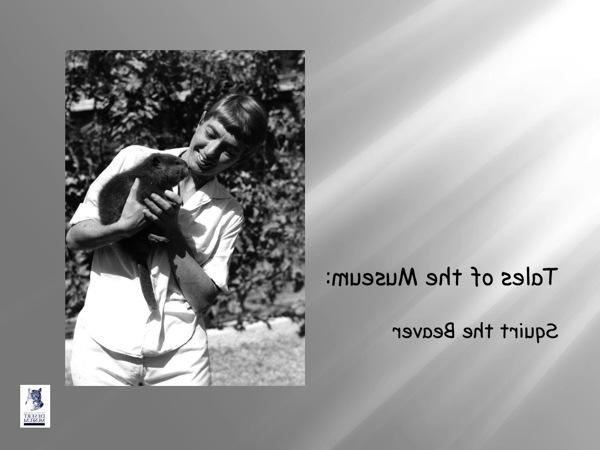

A few years later our family inherited a young beaver eventually destined to join Hal Gras’ Desert Ark, then later to reside in the new beaver exhibit at the Museum. He had been purchased from a “fur farm” (if you can imagine that horror) in the Tetons by our friends the Bartletts who were filming a beaver nature movie for Anglia TV. The new beaver enclosure at the Museum had just been completed and the beaver filming just completed in Wyoming so Merv flew to Jackson Hole, retrieved Squirt the beaver and brought him back to our house, since Hal and Natie were out of town. We gave Squirt one of our bathrooms, let him swim in the bathtub several times a day, and fed him formula out of a baby bottle. Each night near bedtime, I pulled a rocking chair in front of the TV, held him, fed him the formula, and we happily rocked together. Rocking and cuddling a baby beaver with his gorgeous, soft, silky fur was an experience I’ll never forget.

As he grew older Squirt graduated to swimming with our family in the swimming pool. Certainly he could outswim all of us, particularly underwater. He did get distracted occasionally, however, by the skimmer. He could hear the water entering it and was disturbed knowing there was a leak which he knew he should correct and he would attempt to block up the skimmer with objects in the pool!

We also raised a badger for the museum. She was tiny, her eyes not yet opened. She too, received a bottle, later graduating to ground beef, apples, carrots, and dry cat food. Named Franny, after a children’s book character, we gave her one of the bedrooms to live in when we were away during the day, but she had the run of the house when we were home. At the time we also had a mother cat with six kittens in another bedroom and a yellow lab in the garage with eleven babies. That was a memorable spring.

Eventually Franny went to live outside in a walled side yard and dug a burrow under one corner of our house. She loved interaction with us, particularly our kids, and we’d often all visit her on sunny Saturday or Sunday mornings. She was most active at night and I usually fed her about my bedtime. I’d lean over the low divider into her yard and if she wasn’t already waiting there, I’d call, “Franny, Franny” and she would appear. I’d put the food down, but before she ate, she would flop over on her back, exposing her flat, broad, white tummy for me to scratch and she would churr—not purr, but churr with a ch sound.

One Saturday we caught a mouse in the garage. What a badger treat that could be! Real wild food for Franny, I thought. I called Merv and the kids in for this memorable event. I can still see a circle of four pairs of shoes on the kitchen floor—one large pair, one medium pair, and two small pair. We put Franny in the circle and dropped the dead mouse in front of her. She acted a little puzzled, picked up the mouse in her mouth, and cautiously rotated it there a bit before spitting it out. Then, as we watched in amazement she threw up and walked off, with what I interpreted as a disgusted look on her beautiful badger face.

A few years later the bighorn sheep exhibit was finished and the Museum had located a bighorn lamb living on a ranch in Sonora. The rancher agreed to give it to the Museum so Merv and Ike Russell flew down and picked up Chivito. Arriving back in Tucson in the late afternoon Merv brought the lamb home for the night as Chivito was still young and drinking from a bottle. We put him in our bedroom which did not have a rug and played with him most of the evening.

Chivito had been sleeping with the rancher’s children and so decided to sleep with us that night. He took up more than his third of the bed and tended to get down and wander during the night. We didn’t get a great deal of sleep and then when he wet the bed at about 4 a.m. the night was over.

The next morning after getting the kids off to school I went back into the bedroom to get ready for work and by then Chivito was in fine form. He began running around the bedroom, circling its perimeter faster and faster, then crossing the wet bed as a part of each circle, until finally crossing the bed, he then hit the floor and with a gigantic leap banked off the wall above the doorway! Around and around he went. Finally, late for work Merv and Chivito headed for the Museum, with Merv, worried and pondering—if a lamb could clear the top of a standard doorway, then how much higher did the walls of the new sheep enclosure need to be to contain an adult bighorn?

The sheep enclosure was modified and Chivito went to live there. Dagmar Sommers helped care for the birds and mammals, including one of her favorite changes, Chivito. He was still relatively small when one day, while Dagmar was cleaning Chivito’s enclosure, the two of them engaged in some gentle roughhousing. A little later Dagmar realized her wristwatch was missing. As she returned to the sheep enclosure to look for it, she thought perhaps she saw something gold disappear into Chivito’s mouth.

Greatly concerned, Dagmar and the staff watched Chivito the rest of the day, but he exhibited no signs of ill health. The next morning when Dagmar entered the sheep enclosure, something shiny caught her eye. There gleaming from among the sheep droppings was her gold watch! It’s true: It took a lickin’ and kept right on tickin’! No question about it—the watch was indeed a Timex! The only thing lacking in the ASDM sheep enclosure that day was John Cameron Swayze himself. Years later I wrote to the Timex people with what I thought was a great advertising story for them. Evidently that kind of advertising was long past and I never heard from them. I still think that story would have been a winner for them!

Many years later I interviewed Gale Monson who continued a piece of the Chivito story for me and I think it is a prime example of the devotion that the Museum staff and a good many of the animals have exhibited for one another and for the Museum, itself, over the years.

Gale had spent most of his adult life studying desert bighorn sheep in the Kofas and Cabeza Prieta, then when semi-retired had been hired as weekend supervisor for the Museum, and he and his wife lived in the stablekeeper’s house on grounds. In his interview he described his delight when on that morning long ago Merv had entered the staff meeting in progress being trailed by an adorable bighorn lamb.

Since he was living on grounds Gale volunteered to give Chivito his bedtime bottle each night. So about 10 each evening Gale warmed a bottle of formula at his house and, bottle and flashlight in hand, walked through the darkness down to the bighorn enclosure to sit, talk to, and feed the lamb.

In his interview, Gale remembered, “And so I saw Chivito grow and as time went on Chivito and I became friends. I used to sneak down to the lower gate of the Big Horn enclosure and I’d always have a twig of jojoba with me which is one of the things that Big Horn like. As soon as he saw me—there could be fifty or sixty people there standing and looking at him—and if I happened to be in the crowd, he spotted me right away and he trotted right down to me. And that sort of thing was pretty satisfying.”

I invite you as Museum members to think about your experiences with the Desert Museum, to share them with us, and to envision what you’d like the Museum to look like at its 100th anniversary.

Acknowledgements –

We think it is important to acknowledge the contributions of the wide variety of artists who have contributed to the Museum's 'tales' over the years — and especially three who helped contribute to this presentation. So special thanks to Priscilla Baldwin, Jay Pierstorff, and Kenny Don.

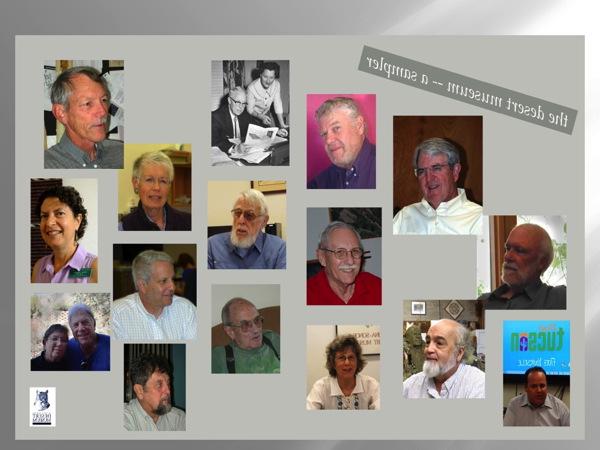

[ACW] In closing we’d like to share with you some of the ‘faces’ of the interviewees over the years. You can see them here and in the lobby on the posterboards displayed there. Be sure to look – you’ll recognize many of the Museum ‘Faces’.

Again to quote Peggy — That there’s been a lot of blood, sweat and tears that’s gone into creating and maintaining this museum — with some laughter along the way.

We hope that you’ll take the time to learn something new about the museum and its history – as we learn from the past – and plan for its future. – Peggy & Anne

For more information, please visit the links on the left hand side — or contact Peggy Larson at 520. 883.1380 Ext. #7284 or plarson@honornm.com.